The Battle Of A Refugee: A Public Health Narrative

By Yawa K., MPH Candidate & Intern, United Nation Association of Greater Philadelphia

People travel to different places or move to new cities or countries for many reasons. Some move to pursue education, others for job opportunities. But for some, relocation is not a choice; it is a survival. For many refugees, starting life in a new country is the beginning of a battle, fought against trauma, isolation, and health needs. The process of healing and rebuilding a life after war has taken everything from you is not always visible to everyone.

This article shares the story of Yousef, a young man born in Damascus, Syria, whose life was reshaped by war and displacement. His journey from Syria to Lebanon, then to the United States and back again to Syria, offers more than a personal narrative. It highlights the public health aspect of forced immigration, particularly, the social, environmental and structural challenges refugees face in the United States. Through Yousef’s voice, we explore what it means to heal when the harm is not only physical, but emotional, social, and systemic.

As of June 2025, the world is witnessing the highest levels of displacement ever recorded. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), global displacement reached 117.3 million people; driven by persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, and severe disturbances to public order. With many living in encampments, prevented from integrating in their host countries Millions of people leave their well-established lives, separated from family, living with memories and scars. They have to start over, hoping that the wounds will heal. The battle of refugees to rebuild their lives is undermined.

Yousef with his parents

From a Normal Childhood to a Life Interrupted

Yousef is the youngest child in his family. Growing up, he was known for his sensitivity and imagination. Yousef was passionate about history and poetry, but these interests did not align with what Syrian society—like many other societies—considered as financially or socially “adequate.”

Yousef always loved writing poems, which he would read to his family. Even though he did not grow up in a religious and strict family, like many families, Yousef’s parents encouraged him to pursue a field that promised economic stability. He enrolled in engineering, despite struggling with mathematics and physics and feeling disconnected from the discipline. His education was difficult not only because of the subject matter but also because of the rigid Syrian academic system, where failing one subject could mean repeating an entire year. Yet, Yousef persevered.

In 2011, the Syrian civil war erupted and changed Yousef’s entire life. Streets that were once peaceful and familiar quickly became places of fear. Kidnapping, bombings and military occupation became part of a whole nation daily life. Yousef was forced to join the army a prospect he found unbearable. “I believe my trait of personality that loves poems is not suitable for war,” he said.

This mismatch between who he was and what war demanded of him was the beginning of his journey as a refugee.

Fight for Survival

In 2013, facing the persistent threat of military occupation, imprisonment, or death, Yousef fled Syria for Lebanon. Like many Syrian refugees there, life was precarious. Employment opportunities were limited, housing was unstable, and legal status remained uncertain. Refugees in Lebanon often live without access to formal labor markets, health insurance, or long-term security, conditions that significantly increase vulnerability to mental health disorders.

For Yousef, the psychological burden began to grow quietly. He left Syria with fear, uncertainty, and grief; not only for the life he had lost, but for the version of himself that war had silenced. Later that same year, Yousef left Lebanon for the United States in search for a better life.

Safety Without Stability

When we talk about the United States, we talk about the “American dream”, the country where any dream can become true. It is often imagined, for refugees, as “the land of opportunities,” and freedom. According to an explainer about the U.S. refugee system from the Council on Foreign Relations: “For decades, the United States was a world leader in refugee admissions. From taking in hundreds of thousands of Europeans displaced by World War II to welcoming those escaping from communist regimes in Europe and Asia during the Cold War, the United States has helped define protections for refugees under international humanitarian law.” Even though the United States offers safety for many refugees, however, safety does not always translate into ease.

At present, many individuals arriving at the United States border and seeking asylum face prolonged delays, with some waiting as long as seven years for their cases to be resolved, according to the International Rescue Committee. During this time, restrictions on employment and limited access to aid programs make it extremely difficult for asylum seekers to sustain themselves and provide for their families.

For over a year, Yousef lived without official refugee status, unable to fully work, study, or plan for the future. The asylum process was long and uncertain. The fear of deportation, of instability, of history repeating itself, became a constant presence. “I always had fear that I will come back to the war,” said Yousef.

Forced migration creates profound fear and uncertainty for many individuals. The lack of legal immigration status prevents many refugees like Yousef from accessing employment, insurance and other essential social services. This absence of stability creates constant stress and anxiety, which can significantly impact physical and mental health, especially in societies where these resources are critical for survival.

Additional challenges, such as language barriers, further exacerbate the burdens faced by many immigrants. As a report from the Center for American Progress notes, the lack of adequate interpretation and translation services for asylum-seekers who are not proficient in English impedes their ability to navigate the complex immigration system.

In Philadelphia

Limited access to employment often results in restricted healthcare options and poor living conditions, compounding the difficulties experienced by displaced populations. Yousef shared what he faced in terms of housing. He moved frequently, between Northeast Philadelphia, Manayunk, Chestnut Hill, and even New Jersey, seeking affordable rent and human connection. Housing insecurity is one of the most significant challenges faced by refugees in the United States, and it directly impacts health outcomes. Without stable housing, it becomes difficult to maintain employment, access healthcare, or establish social networks.

Additionally, many refugees often end up living in substandard housing, where they share spaces with multiple people. This increases the risks of disease transmission. Moreover, living in an unsafe environment exposes them to higher levels of pollution, limited access to quality healthcare, and constant threats of violence or substance misuse. For someone fleeing war and trying to rebuild their life, access to safe and stable housing is essential for both physical well-being and emotional recovery.

For someone fleeing war and trying to rebuild their life, access to safe and stable housing is essential for both physical well-being and emotional recovery. How can someone heal and start over when they are constantly on the move or lack a place, they can truly call home, a place where they feel safe and secure?

The vulnerability of refugees forces them to work in poor conditions where they are underpaid or overexploited. Yousef worked multiple jobs, at an olive oil store, a cricket club, and as an interpreter for Syrian families, often in positions that did not match his skills or aspirations. He wanted to pursue his education but couldn’t get scholarship and resources to attend a community college. “America is good, but it’s a long walk.” This “long walk” reflects what public health refers to as the structural vulnerability; the way social systems systematically limit access to resources for certain populations.

Loneliness, Trauma, and Mental Health

Perhaps the most profound struggle Yousef faced was loneliness. He described nights alone in cold apartments, haunted by memories of war and separation from family. Over time, this isolation deepened into major depression. Yousef was eventually diagnosed with major depressive disorder and experienced symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder. Studies estimate that 30 to 40% of refugees in high-income countries suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, or depression, compared to about 10% in the general population.

Accessing mental health care in the United States is challenging. Insurance barriers, cultural differences, and the shortage of trauma-informed services for refugees limited his options.

While he did see therapists and receive antidepressant medication, healing remained incomplete. “In 2018, I fell down completely,” shared Yousef.

Community as Medicine: The Power of Human Connection

What ultimately helped Yousef survive was not only therapy, but his community. Yousef joined religious groups, trying to understand each groups’ perspective. Through his involvement, he met people that helped him navigate through his journey and share his story.

During one a meeting, he met Helene, an older American woman who became a close friend, advocate, and source of stability. She helped him navigate job applications, translate his poetry, and even supported the publication of his poetry book.

Yousef actively sought connection, visiting different religious and civic groups not to convert or belong to one identity, but to understand how people lived together and supported one another. For someone coming from a society where civil institutions were weak or fractured by war, these spaces offered a sense of structure and human warmth. Helene recalls that even then, Yousef carried himself with deep thoughtfulness and empathy, qualities that shaped how others responded to him.

Yousef with Christiaan Morssink, UNA-GP President

Yousef also found belonging through the United Nations Association and interfaith spaces, where he was invited to speak about his experience as a refugee. Through this association, Yousef met Bob G., Christiaan M., and many other people that helped him share his story and feel less lonely. These relationships reflect how social support is a protective health factor. Refugees with strong community ties demonstrate lower rates of depression and better long-term integration outcomes.

Bob G., a former member of the UNA-GP Board, met Yousef through community and refugee advocacy work in Philadelphia. Their interactions were simple—shared meals, conversations at and event—but they left a lasting impression. Bob recalls Yousef as warm, thoughtful, and easy to talk to, someone carrying the weight of displacement quietly while trying to build a life on his own. Even without knowing all the details of Yousef’s legal status or mental health struggles at the time, Bob sensed the challenges he faced. He admired Yousef’s resilience and openness, noting how, despite uncertainty and loss, Yousef remained engaged with others. His experience reflects the reality of many refugees whose strength is often visible, while their emotional and psychological struggles remain unseen.

Bob emphasizes that Yousef’s struggles were shaped not by personal failure, but by systems that define refugee life in the United States. His reflections highlight a central point of Yousef’s story: resilience alone is not enough.

When dignity, connection, and community are present, healing becomes possible, and refugees are revealed not as problems to manage, but as people whose well-being is tied to the health of the society that receives them.

Pets, and the Meaning of Healing

While living in the United States, Yousef also discovered a world where pets are not simply seen as animals, but more as companions. He really enjoyed taking care of people’s pets and have them around. This made him feel less lonely.

Yousef spoke on the injustice toward pets : “In the Middle East, animal protection laws are weak and abuse is still common. Society often does not treat animals as friendly companions, and the school system provides little education on how children should care for and be kind to pets. Pet stores are often among the worst places for animals, where they are kept in cages with little food, no medical care, and poor living conditions.”

Yousef speaking about the injustice facing pets in the Middle East.

Animals play an important role in many people’s lives. In addition to seeing-eye dogs and dogs that can be trained to detect seizures, animals can also be used in occupational therapy, speech therapy, or physical rehabilitation to help patients recover. Interacting with animals has been linked to reduced cortisol levels (a hormone associated with stress) and lower blood pressure. Other research suggests that animals can help alleviate feelings of loneliness, enhance perceptions of social support, and improve overall mood.

Return to Syria and Poetry

After years in the United States, Yousef made the difficult decision to return to Syria, primarily to care for his aging parents. By then, he had been exempted from military service. Returning was not a step backward, but a redefinition of healing.

Back home, despite fewer medical resources, Yousef found a role within his family and community—caring for his parents, reconnecting with old friendships, and helping abandoned animals survive. His emotional well-being improved not because his past trauma disappeared, but because he regained dignity and purpose. From a public health lens, Yousef’s journey raises an essential question: how can host countries create conditions where refugees are not only safe, but truly able to belong, contribute, and heal?

In Syria, Yousef began caring for abandoned cats and dogs, animals often neglected in a society struggling to recover from war. This work became a form of therapy, grounding him in compassion and purpose.

“I felt like I was an abandoned cat or abandoned dog,” Yousef reflects.

“Part VI Freedom

I see existence only as a stolen painting in the rivers behind the dams.

Someone stole it – someone who found neither answer nor response.

He crossed the bridge of death and jumped over the borders.

He bid farewell to his life and his companion, and places a kiss from his lips on those cheeks.

He gave them stalks of wheat and a bouquet of roses.

He grabbed a sword and tore up his book of memories and went away forever, forgetting his past and his promises.”

Through his poetry and activism toward animals, Yousef transformed his trauma into a connection.

One Story, Among Many Others

Yousef’s story highlights broader systemic issues affecting refugees in the United States. Mental health services are insufficient and difficult to access or not designed to address trauma caused by war and displacement. Even when help is available, language barriers, cost, and long waiting times prevent many refugees from receiving consistent care. As a result, emotional pain becomes a silent burden, worsening conditions such as depression, anxiety, and chronic stress.

Eventually, Yousef was able to access to medical and mental health care that many refugees today struggle to obtain. He received treatment for physical injuries related to the war and later accessed mental health services when emotional distress became overwhelming. Helene emphasized that this level of access was possible because United States refugee policies and public health services were more accessible at the time of his arrival. From a public health perspective, Yousef’s experience shows how critical early and sustained access to care can be for refugees dealing with trauma. Yet, even with professional support and a strong network of friends, healing remained incomplete, highlighting that clinical care alone cannot address the deeper impacts of displacement and loss.

What Helene observed most clearly was the role of social connection in Yousef’s well-being. He formed meaningful relationships with Americans across ages, backgrounds, and faiths, and these relationships helped him navigate daily life, language barriers, and moments of deep loneliness. Still, Helene noted that Yousef’s experience was unusual. Many refugees do not have the same social skills, language proficiency, or opportunities to build such broad networks. Public health systems often assume that individual resilience and community goodwill will fill the gaps left by limited institutional support. Yousef’s story challenges this assumption, showing that even the most socially capable individuals can struggle when stability, purpose, and sentiment of belonging remain fragile.

Employment options rarely match refugees’ skills. This mismatch affects not only economic stability but also long-term well-being. Housing insecurity exacerbates psychological distress. Without strong institutional support, social integration depends heavily on informal networks, such as friends, faith groups, or volunteers. While these networks can be life-changing, relying on them alone places too much responsibility on personal resilience rather than on systems designed to support healing and stability.

In The Truth About Immigration: Why Successful Societies Welcome Newcomers, Zeke Hernandez argues that immigrants and refugees are not burdens, but contributors whose well-being directly affects societal prosperity. When newcomers are supported, through education, healthcare, and inclusion, societies benefit economically, culturally, and socially.

Yousef’s life embodies this truth. Given support, he contributed through his art, advocacy, caregiving, and community engagement.

Yousef’s story is not just a narrative; it is representative of the reality that faces many refugees. Healing after war is not only about escaping violence. It is about restoring dignity, connection, and meaning. For refugees in the United States, we must move beyond emergency care to address the structural and emotional realities of displacement.

“If there is a place where refugees could stay with dignity,” Yousef says, “that would change everything.

In listening to Yousef, we are reminded that public health is not only about policies and statistics. It is about people, and the quiet battles they fight long after the war ends.

“Part V Happiness

I don’t know what has already happened, and what’s happening now.

Sadness like blood walks through my body.

My universe darkens like a fish – and the blackness is my river.

My chest and heart become narrow from pain and love. ”

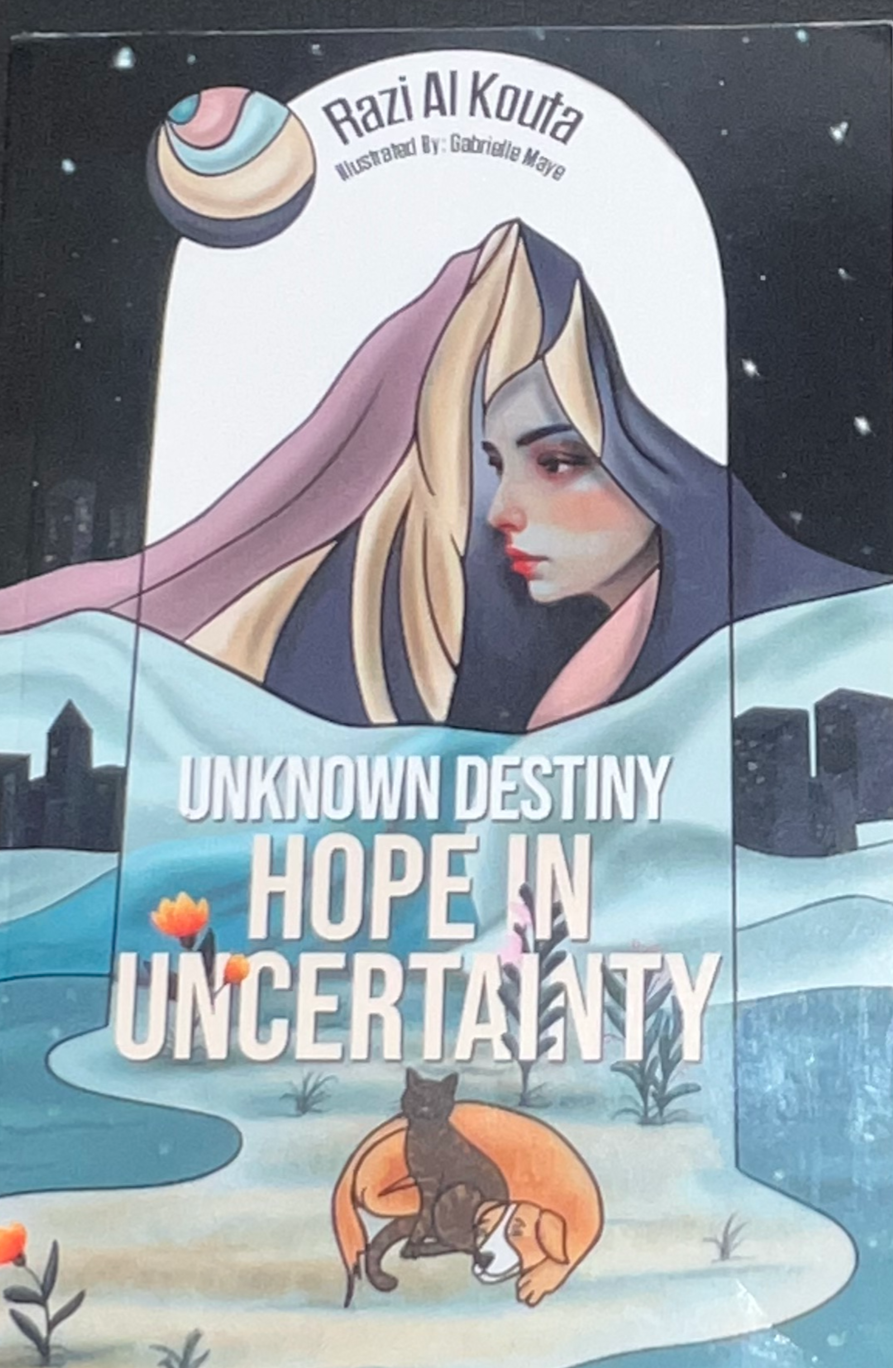

Al Kouta R. Unknown Destiny Hope In Uncertainty – Yousef’s poetry book

We think happiness comes for moments. That satisfies us, but happiness has warned us, “I can cheat on you and leave you in your sadness, alone”.

The shy shines for a moment to light up my life now that my crescent moon has died.”